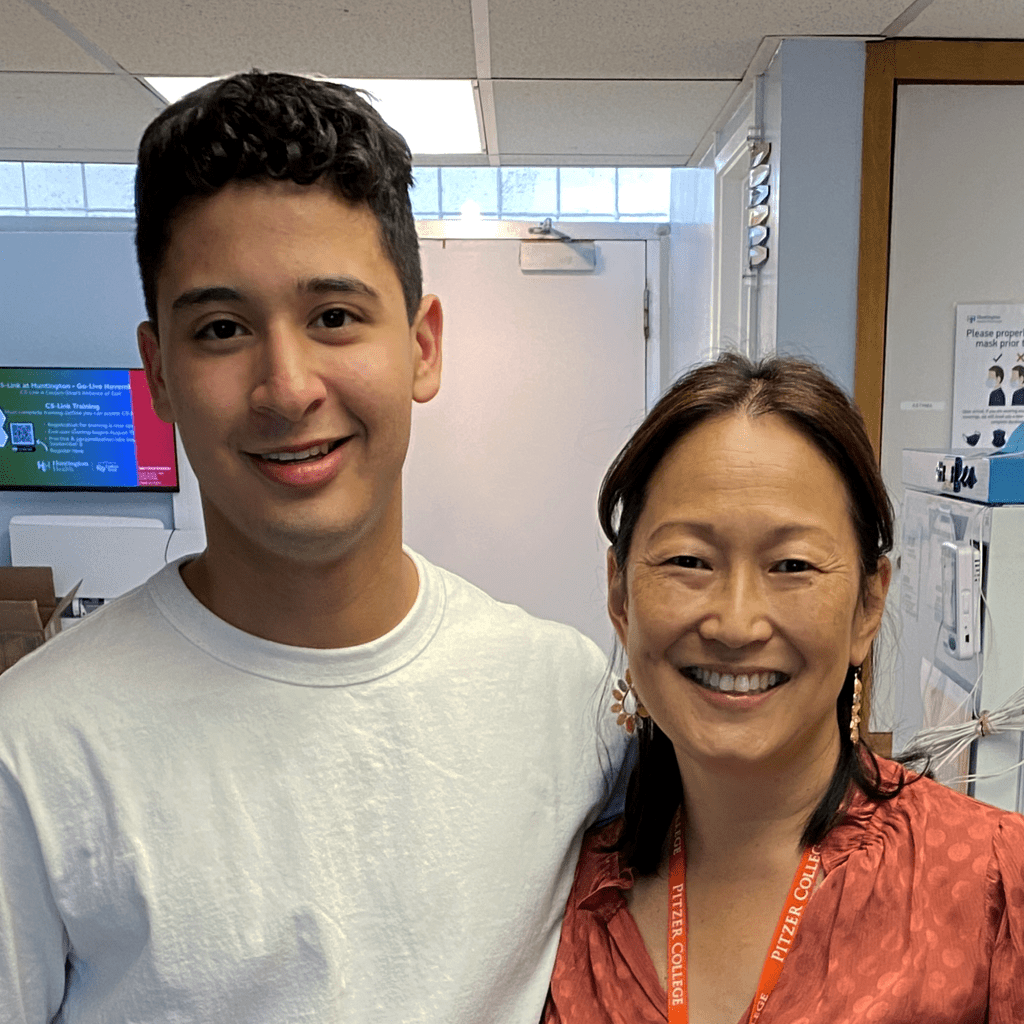

We all know how taxing pursuing medicine is. In their formal education alone, a doctor spends eight years toiling through tough courses, challenging their brains to retain boundless information, and studying for a never-ending list of exams. From dawn until the bitter fringes of the night, the only social life a medical student seems to lead is that shared with the pages of a textbook. And any solace found can quickly disappear. Initially, finally graduating with a doctorate. seems like the finish line. However, as the distance closes, the mirage fades, and a distressing truth comes into sight. The finish line was really just a checkpoint. There’s still another half of the race left to run. Except now, it’s no longer a marathon—it’s cross country. Having recovered their stamina for a moment, the doctor sets off into the hilly terrain of their residency. To keep them refreshed throughout, they’re provided a cocktail of more all-nighters and relentlessly tight schedules, with a shot of fear of failure to pack a final punch. This path can seem even more daunting for those of us interested in becoming surgeons. According to the American College of Surgeons (ACS), even after eight years of schooling, all surgeons spend a minimum of four years in residency training, with most specialties requiring upwards of five years.1 Afterward, sub-specialist surgeons continue onto fellowship programs, further contributing to the length of their preparation. We know well that it is no joke. Simply put, any aspiring doctor is poked, prodded, stretched, bent, and tested in all other sorts of manners before they even finish their training. So, no matter how passionate we are, it’s only natural that we may question if this is really the career for us. But, talking with a trusted doctor can provide much guidance. I had the privilege of speaking with Dr. Jean Chou, a wonderful pediatrician with the Huntington Health Group. Her experience speaks to the multiple struggles of medicine, and how to work through them. Although her take on why one should pursue medicine is one of many, I strongly believe that it’s a stance worth considering. As she explained to me, it’s quite simple. No, it’s not decided by an online quiz that guesses if surgery is a good fit for you. It’s not the prestige that comes with having “M.D” or “D.O” at the end of your name. And it’s definitely not the allure of the wages that consistently top national rankings. Rather, it’s your own answer to a very plain question—does medicine itself make you happy?

Even before you apply to undergraduate school, you should be able to enjoy the venture you will embark on. Central to the career, there needs to be a passion that is fed and nurtured by all the studying that comes along with it. It will be upwards of twelve years before you can fully practice medicine. “[That] is a huge chunk of your life…,” Dr. Chou emphasized. “I would hope that you’re still liking it as you’re doing it, and I think the only way you will is if you’re really enjoying all the learning.” This becomes increasingly important as the educational track snowballs into an ever-larger time commitment. There’s only twenty-four hours in a day, and sacrifices often have to be made for what is done with that time. To keep these choices from becoming a burden, it is invaluable that you are fond of what’s on the academic end. For instance, let’s consider socializing. Throughout a doctor’s studies, missing out on the biggest adventures their friends are having might become a regular occurrence. That’s not to say they must become hermits. In fact, it would be detrimental to completely isolate themselves, both for their mental health and academic success. However, they might need to give up partying, traveling, and similar events that take away substantial—and, therefore, necessary—amounts of study time. And when deciding if this is the career for you, you need to be willing to work through that. Per Dr. Chou, “[Medicine] is your life—and you have to be okay with that!” If medicine is a passion of yours, then you’re priming yourself for a successful career. You still might grow tired from overnight study sessions, all the tests you need to pass, the long shifts of residency, or even from having to deal with insurance companies on patients’ behalf, but a love for medicine helps to hedge against a major consequence of this fatigue—burnout. The American Medical Association (AMA), defines burnout as a condition caused by long-term stress. Its symptoms can include emotional exhaustion, apathy towards patients, and a devastated sense of personal achievement.2 The AMA also placed doctor burnout rates at 63% in 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic increased medical workloads nationwide during that year, marking this figure as a partial result of extreme and unusual circumstances. But in pre-pandemic 2020, the number was still 38%.3 Even without such a grueling strain being placed on the country’s physicians, over one in every three doctors suffered from burnout. The trend is similar for surgeons, too. Dr. Tait Shanafelt and his collaborators found that, of 24,922 surgeons surveyed from the ACS’s member body, 40% suffered from burnout. Further, symptoms of depression were exhibited by 30% of that same sample.4 There are both interpersonal and intrapersonal consequences to this. Most obviously, if a doctor isn’t able to provide a patient with the greatest capacity of care possible, the patient suffers. At best, the patient doesn’t receive the proper treatment they deserve; at worst, it can cost a patient their life. Disregarding that however, burnout’s impact on a doctor’s mental health cannot be understated. When a career is so demanding, any symptom that burnout causes is magnified. Medicine takes up so much of a doctor’s life that it becomes almost impossible to alleviate the pressure causing these wounds. Dr. Chou succinctly noted that if a doctor hates their career, it becomes a chore to work through, and the life they lead grows miserable. I then asked what kept her from suffering from burnout and allowed her to push through her training. She responded, “I’m very much someone who likes to enjoy what I do. So, I wasn’t that person that had to go to this med school and that residency program…I just did what I found interesting. In college, that was biology. In med school—I just loved all of it…” She concluded, “Honestly, only do it if you really like it. If you hate it, then maybe pick something else, because it is a life-long dedication, and I don’t think there are any guarantees that once you become a doctor you’ll love it.”

This piece of advice shouldn’t be a factor only when considering whether to become a doctor at all. It should be a roadmap we rely on for the entirety of our trek. For a lot of us, there can be much pressure—from our friends, our families, and even ourselves—to attend the most honorable and recognizable schools. After all, who wouldn’t want to be an Ivy League doctor? Just like with a medical career, though, we should only chase a school if it’s the right fit for us. Contemplate what a school can provide you, not its prestige. Variables to look at could include: what programs from the school pique your interest; what research opportunities the school hosts; how competitive the culture among students is; how you would fit in with those peers; how large and what style of classes you would take; whether the school tenures unique specialists in subjects that excite you; and even how busy professors tend to be. The location of the school is another important component to examine. Even among the top schools in the nation, this can vary significantly. Take two Ivy Leagues within the same state, for example—Cornell University and Columbia University. Both are in New York. But, Cornell is in Ithaca, over two hundred miles from New York City. Meanwhile, Columbia sits right in the heart of Manhattan. This distinguishes the experiences at each school significantly. Simply living in a metropolitan city would be enough to attract or utterly disgust different people. There’s much more to these schools than their names. Besides, it often doesn’t carry the greatest impact on your career. Dr. Chou handles the physician management at her clinic, which includes hiring new doctors. She tends to disregard which schools an applicant has attended. “I’m looking at your letters of recommendation,” she elaborates, “and, when I talk to you, are you engaged, do you seem caring? Are you willing to work extra to be that great doctor?…You got through [med school], you know the material, so if you come off as a dedicated person who’s kind to the parents and families, a team player, a great communicator—that’s what makes you a great doctor.” Sure, attending a school with a stand-out reputation shows programs you apply to that you are a serious worker capable of handling tough challenges. But, there are a plethora of alternate ways to communicate this, often even more effectively. At its core, a school’s name is only a supplement that confirms what your profile already says. If it isn’t there, a stellar CV more than makes up for it. Seldom does it play the role of the sole determinant. Such a faulty promise of glory isn’t what a decision of this magnitude should rest upon. It should depend on your academic and personal needs. “If you’re going to go to Stanford and struggle…that doesn’t help your self-esteem or your happiness.” Dr. Chou continued, “If you go to a different school that isn’t as well known, but seems like a better fit for you, you’re gonna be happier in your life and you’re still gonna get the education…It’s your life, and you want to be happy through all of it, so find a place that fits you, as opposed to a name.”

A similar push can exist when choosing a specialty. Questions in the vein of “Why choose [any lesser known specialty] when I can be a cardiothoracic surgeon, or a plastic surgeon?” pass through the minds of many. But, Dr. Chou recommends that self-fulfillment once again be the only element influencing your decision. If cardiothoracic or plastic surgery is truly your calling, go for it. But, if you have decided on a specialty because you aren’t sure if you should chase something else, then it might be time for a re-evaluation. Shadowing, internships, and volunteer experiences are all great ways to familiarize yourself with the day-to-day of various surgical careers, and in your residency, you will rotate through many departments of your institution. Even for those of us set on a certain specialty, these experiences should be met with open arms. “Maybe you do a rotation, and you’re like, ‘Woah, this is so cool!’, or ‘I never knew this even existed!’…You shouldn’t be closed off to taking everything in,” Dr. Chou advised. This is similar to why she advocated for getting experience before you fully commit to medicine as a whole. “[If you liked research, for example,] maybe you should go to an academic center where you can stay there and do research. Or did you just like the clinical part?” She chuckled as she continued, “And if you did, maybe you’ll like a job like mine better.” These opportunities help you define exactly what you want to do with your life. You don’t have to commit problematic amounts of time to them, either. She notes that even one afternoon per week can be extremely illuminating. It provides insight that wouldn’t otherwise show itself—and this insight is vital as you dive deeper into the field. The dedication a medical career requires should be spent on something you know you’ll love. Embrace getting your feet wet as a chance to find what your interests crave.

Medicine is for those who truly love it—that was the theme of my discussion with Dr. Chou. “It all just circles back to your point, that, if you’re happy, you’re going to get through it,” I noted towards the end of our discussion. In delighted agreement, she smiled, and simply responded, “Exactly. It’s super important!” Certainly, a medical career will make you question if you’re headed in the right direction. We know the challenges we will face. From the sheer time commitment, to the drain from physical and mental demands, it stands at the opposite end of the Earth from effortlessness. Struggle, strain, and stress are the cornerstones on which a doctor is built. But a structure of any size crumbles if the ground underneath it trembles easily. Without a passion for medicine, trudging through it simply won’t be worth enough to keep you motivated. So, even when they feel infinitely overpowering, the doubts felt aren’t what should be considered. Rather, it should be whether you are doing what truly makes you feel happy—what fulfills you. Undying love for the field must be the unwavering ground upon which the entire structure of a doctor’s life rests. Under any force, it does not give way; it empowers them to bear the weight of a heavy career.

References

- “How Many Years of Postgraduate Training Do Surgical Residents Undergo?” FACS.org, https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/education/online-guide-to-choosing-a-surgical-residency/guide-to-choosing-a-surgical-residency-for-medical-students/faqs/training/#:~:text=Once%20medical%20sch

ool%20has%20been,a%20minimum%20of%20five%20years. ↩︎ - “What Is Physician Burnout?” AMA-Assn.org, 16 Feb. 2023, https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/what-physician-burnout. ↩︎

- “Measuring and Addressing Physician Burnout.” AMA-Assn.org, 3 May 2023, https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/measuring-and-addressing-physician-burnout. ↩︎

- Shanafelt, Tait D et al. “Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons.” Annals of Surgery vol. 250,3 (2009): 463-71. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ac4dfd. NIH.gov, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19730177/. ↩︎